Personal status and nationality laws

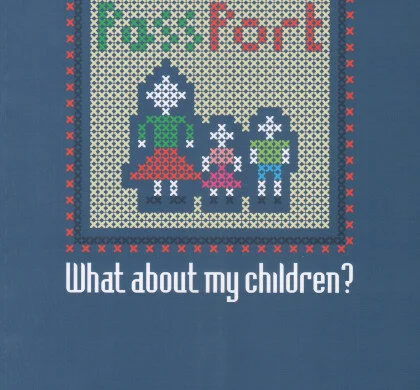

Much of the inequity that women face in the region has its root in openly discriminatory family law. Such laws deepen economic inequality, do not adequately protect children from forced and early marriage, and see women face iniquitous consequences in cases of divorce and child custody.

So many of the divisions and inequity between men and women in our region are set in laws concerning the family.

Often called ‘personal status laws’, these statutes cover many aspects of basic interactions people will have with the law, such as marriage, divorce, and child custody. Too often they set fundamental precedents that mean women enjoy fewer rights and cannot expect equal treatment.

In certain countries, personal status laws can allow for the marriage of girls as young as 9 years old. This can be explicit within the law, or the legislation may allow judges or officials the discretion to permit marriages below the statutory age.

Our partners AWO are building support to end inequity in Jordan’s nationality law, as in the above work.

Ending unfair and inconsistent law

Occasionally these laws will even set different standards and precedents within a country. In Palestine, two different personal status laws are enforced - both deeply anachronistic. In the West Bank, the Jordanian Personal Status Law of 1976 is applied, while in Gaza it is the Egyptian law of 1936. In Lebanon, different laws are in force for each of the country’s sects, meaning that there are fifteen separate personal status laws on the statute.

Our colleagues in Palestine and Lebanon are campaigning for modern, unified laws to provide equality and consistent standards of rights and justice.

Inequality can also be found in nationality laws. In countries like Jordan, if a woman is married to a foreigner she is not able to automatically confer her nationality on her spouse or her children. Jordanian men married to non-Jordanians do not however face the same restrictions. This jarring inequality has serious impacts on basic rights and entitlements, with children considered foreigners even if they were born in their mother’s homeland, denied the same rights to education and economic opportunities as their peers. The ramifications can be even greater in cases where custody is disputed.

Even in countries that have amended their family laws more recently, activists are mobilizing to demand urgent changes.

Morocco revised its personal status law into the 'Moudawana' - the new family law - in 2004. This made a number of changes that women's rights activists had campaigned for, such as removing requirements on women to have consent from their “guardian” in order to marry.

Our partners in Morocco are campaigning for amendments to the Moudawana that would, amongst other things, ensure there can be no derogation whatsoever from the legal marriage age of 18, and abolishing articles that mean divorced mothers relinquish their custody rights if they remarry.